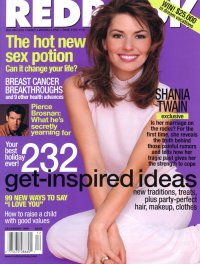

She's Still The One

Her rags-to-riches story seems like a fairy tale: Shania Twain has overcome countless tragedies and seemingly insurmountable obstacles to reign

triumphantly as one of the country's hottest divas.

Her rags-to-riches story seems like a fairy tale: Shania Twain has overcome countless tragedies and seemingly insurmountable obstacles to reign

triumphantly as one of the country's hottest divas.

Shania Twain should have been ecstatic. The Canadian country-pop singing phenom was in the middle of her first major tour, which would eventually sell more than a million tickets worldwide; her third album was still dominating the charts two years after its release; and she was about to sign a big modeling deal with Revlon. But as the 14-month tour went on, she says, "I was really depressed. I felt so isolated, like I was in this little bubble. You have to give up on the fact that you don't have any freedom or it'll just

drive you crazy. And it did, at first."

Away from her husband and musical collaborator, Robert John "Mutt" Lange, for stretches of three to ten weeks at a time--he was busy working with everyone from Def Leppard to the Backstreet Boys and supervising renovations on their recently acquired "mini-castle" in Switzerland--Twain was feeling very "disconnected," she says. "You're talking to this person on the phone who's not part of your everyday life. It's really awkward."

But Shania Twain has never been one to succumb to the blues. After spending most of her childhood poor and hungry, then raising three younger siblings after her parents were killed in a car crash, Twain, 34, willed

herself to become not just one of the biggest-selling female country artists ever, but a crossover sensation, the first woman ever to have consecutive albums sell more than 10 million copies each in the United States (1995's The Woman In Me and 1997's Come On Over, now at 13 million and still selling).

To conquer her on-the-road funk, Twain played celebrity hooky: She'd leave the arena where she was rehearsing and walk around the streets by herself. "I didn't tell anybody where I was going, people didn't have tabs on me, no security," she says. A few times she even found herself forced to enter the concert hall alongside thousands of fans. "It was exciting," she says. "I thought, Wow, I'm right with these people, and I'm getting away with it."

And the next time she hits the road--after taping a TV special for CBS that will air on Thanksgiving Day, she's off for an impromptu two-or three-week mini-tour of the United States--she hopes to bring her husband

along. "I feel much more connected with Mutt," she says. "Your partner is your--not your lifeline, I don't want to be that dramatic--but you base your life with your partner."

The love of her life

People have sniped at Twain's relationship with her husband from the get-go, suspicious of the whirlwind romance, the age difference (at 50, he's 16 years

her senior), and the long separations, convinced she's merely Lange's music puppet. Her

marriage-slash-partnership with him has become regular fodder for speculation in the supermarket tabloids. Most recently, a "Shania Twain Divorce Shocker" cover story in the National Enquirer reported that when she

returned to her hometown of Timmins, Ontario, this past summer and saw a man she'd dated for five years when she was in her 20s, he fell back in love with her and suddenly deserted the mother of his children--and that Twain's marriage was sure to end.

"What bothers me the most is that people take

[tabloids] seriously," Twain says. She admits that she did briefly see an ex-boyfriend the tabloid

unearthed--and his girlfriend--when in Timmins and that the two did split up afterward. "But it had nothing to do with me," she insists. "It's not fair for innocent people to be exposed and harassed like that." As for Lange, Twain says he doesn't care about the

insinuations about their marriage. "It's not new," she says. "I think people don't want it to work, because

we're so successful as a team, because of the age difference, because of the fact that we work together."

Twain has never had a conventional love life. "Growing up, I was serious about my career and my life," she says. "Men were always secondary. I never put a man first, ever." She only met her husband through what might be termed a very expensive video dating service: Lange saw her 1993 video for "What Made You Say That" and called her from England. During an extended

phone courtship, he encouraged her to record more of her own songs. When they finally met in person, it didn't take long for them to fall in love. They spent their first six months together traveling around Europe and collaborating on what would become The Woman In Me, a sort of honeymoon album. They married in December 1993.

"We are definitely a good example of the saying 'opposites attract,'" says Twain. "We're one of those couples where, if my inclination is to turn right, his is to turn left. If we order water at a restaurant,

he'll say 'avec gas' [with bubbles] and I'll say 'sans gas' [without]." But when they argue about, say, which single to release, "we just end up talking it through."

"Because he's more experienced, a lot of people had the opinion he was in control of the situation," says Danny Goldberg, former head of Mercury Records Group. "But after meeting them, I realized she's very much his

equal. He's doing her bidding as much as she is doing his."

"It's a really healthy relationship," attests Luke Lewis, the president of Twain's label, Mercury

Nashville. "They're both very forceful, bright people, and they respect each other." He believes Twain's biggest hit, "You're Still The One," is a thinly veiled reaffirmation of their love the naysayers.

The key lyric about their relationship might be "I can't always be the rock that you see," from "The Woman In Me." Lange, says Twain, taught her how to be vulnerable. "There's something very settling about finding the person you're going to spend the rest of your life with," she says. "I became much more relaxed. The challenge of finding someone to understand me was over. When you're striving to become something in life, you have to be this liberated, strong woman. Now I don't have to be so independent to feel I'm worth something, and that's a big change."

Twain says she didn't feel fully comfortable in her relationship with Lange until she had achieved her own financial success. "There was no way I was going to enjoy life beyond my own personal means," she says. "He thought it was ridiculous. But I worked my butt off, and now I'm independent financially. I can help my family with my money, give to charity with my money."

During her last tour, some of the proceeds from every concert were donated to local charities that aid hungry kids. The connection is intensely personal. "I was that hungry kid," she explains. "My goal is to save kids

the humiliation, the anguish of feeling inferior." And backstage after every two-hour-plus performance, Twain amiably worked her way through a line of dozens of well-wishers, including an autistic child and a jaundiced, dying man on a stretcher whose last wish was to meet her. "A lot of artists [wouldn't meet with a dying fan], and I can understand why," she says. "But

I've been through enough in my life that I can relate to people very well. I'm not tough. I'm strong. And I think there's a very big difference."

From rags to riches

If Twain's life story were a TV movie no one would believe it. "We had a fairly unstable upbringing," she says, adding, " 'fairly' is probably a mild word." She was born Eilleen Regina Edwards on August 28, 1965, in Windsor, Ontario, the second of three daughters of Sharon and Clarence Edwards, a railroad engineer. Her parents divorced when Eilleen was a toddler; Sharon

moved with her girls to Timmins, a woodsy mining town 500 miles north of Toronto, and married Jerry Twain, an Ojibwa Indian who scratched out a living as a forester and prospector. He adopted Eilleen and her sisters, and he and Sharon added two sons.

Twain grew up regarding Jerry as her father; even friends only learned of the existence of her biological father after the Timmins newspaper exposed it a few years ago. (The tabloids then implied she had kept her "real" father a secret to exploit her adopted father's Indian heritage.) When she was eventually offered a record deal, she decided to change her name to make

it more business-y. "Shania" is an Ojibwa name that means "I'm on my way."

The road from Timmins to Nashville was, as a country singer might put it, paved with heartache. Jerry was regularly out of work but too proud to accept and form of public assistance; Sharon was often depressed.

"Most kids feel inferior if they don't have the right jeans on," says Twain. 'I was way beyond that. I was worried about what was in my lunch. Nobody knew we were hungry, and I did everything I could to hide it," often bringing a mustard sandwich to school. She remembers referring to the rich as "roast beef families." (Ironically, now that she can finally afford roast

beef, turns out she's sworn off the stuff. Following Lange's lead, she's become a vegetarian. "Spiritually," she says, "I think there is something odd about eating another anything.")

Her older sister, Jill, left home at 14, making Eilleen, then 12, the oldest by default. "We were probably in the heart of our difficult times as a family," Twain recalls. "I had to take control and was really an anchor in keeping the family together."

Twain's talent proved the family's salvation. At 3, she would sing along with the local diner's jukebox. Her parents, especially her mother, encouraged her, dragging her out to perform in community centers, senior citizen homes, even local clubs. "Our mom had a lot of faith in her," says Twain's younger sister, Carrie-Ann Brown, 31. "She was always on the phone

trying to book things, taking her to talent contests, traveling out of town to shows, getting her lessons. And Shania would always be singing--even just walking down the street. I'd be embarrassed."

By 8, Eilleen was making money by performing; by 10, she was writing her own songs. Her first two titles--"Is Love a Rose?" and "Just Like the

Storybooks"--are evocative of a girl wondering whether the promises of songs could ever come true for her. She fantasized about being kidnapped by Frank Sinatra, who to her epitomized showbiz wealth. "I wanted to escape this life I had," Twain says, "and I knew the only honest way of doing it would be to be kidnapped. Because I'd have felt so guilty if I'd ever left my family willingly."

Since Sinatra never came, "I learned to be a survivor," she says. "You learn that you cannot depend on anybody else to make things happen for you." Through it all, she insists, she never resented her parents. "It's not like they were never there. They wanted things to be right. The fact that they sometimes couldn't feed us must have torn them to pieces."

On weekends during high school--where, she says, she was an average student who spent a lot of time locked in a music cubicle writing songs--and after graduation, she played in bar bands that covered top-40 and rock songs. The audiences were full of drunks, but she didn't mind. "There's something more moving about music than anything else in life for me," she says. "It's

like a drug. I spent my teen years being high on music."

Music has seen her through hard times, and it remains a vital source of inner strength. She calls it her

therapy. "I've never seen a shrink,"

Twain says, "even at times when I think maybe I should have. I don't want to sound weird, but music can do more for me than any person ever could."

Her life changed forever in 1987, when the car her parents were driving collided head-on with a logging truck. At first, 'I was kind of numb," Twain says. Though not a religious person, she says what helped keep her going was the belief that her parents "had gone to a better place." Since she was 21, custody of Carrie-Ann, then 18, and half-brothers Mark, 13, and Darryl, 14, fell to her. "I had practically raised them anyway," she says, but still, "it was a lot for me to deal with. It now seems like another lifetime--like

I'm talking about another person."

There was some insurance money, and Twain landed a job performing regularly at Deerhurst, an Ontario resort that staged Vegas-style shows. She started earning about $ 30,000 a year, enough to buy a car and a small house. The plumbing didn't always work, but it was a definite step up. "We weren't starving," she says. "I actually look back at that time very fondly."

One recent tabloid article suggested that the man who ran Deerhurst paid for her teeth to be fixed and put her up in a condo. "It's completely false if they're insinuating I had an affair with him," Twain says. "What probably happened was that I needed a raise because I was getting my teeth done. But I certainly paid my own dental bills.:" As for the condo, she

said, "My parents had just died, and until our house was ready, I was allowed to keep my family in one of the units there for a couple of weeks. [The

tabloids] make it sound like I was the young mistress locked away in the penthouse!"

It was at Deerhurst that Twain was discovered, thanks to an old family friend who had a record business contact in Nashville. It's also where she confronted her long-standing shyness about her body and bared her navel for the first time: playing the Indian in the resort's Village People tribute.

"I went through a stage as a teenager where I resented the fact that there was a difference between men and women," Twain says. " I just wanted to be a person. I was very athletic, and I would always strap my breasts

down so that when I was on the football field, the guys were watching me play, not watching me bounce. On a hot summer day, I'd wear something over my bathing suit, and the when I'd get into the lake up to my knees, I'd throw it off and dive in."

But being backstage at the resort, "I just got used to seeing people be so comfortable with themselves. Having to change in front of all these girls, I got forced into just getting over it."

To a point. She may now be a video and photo-shoot sex kitten with a navel-barring, leopard-print wardrobe (which recently helped land her on People magazine's worst-dressed list, alongside Mariah Carey and Madonna), but underneath, she's still something of a prude. In the video for "Man! I Feel Like A Woman!" she wore a short skirt--with bicycle shorts underneath. "I'm still very conservative when I'm not performing," she insists. "Like on the beach, I don't like people looking at my body."

Twain says she brings the same approach to her songwriting: Her songs, she insists, are not deeply personal or autobiographical. "I'm not that dramatic," she says. "I don't feel the nature to communicate my innermost feelings--and they wouldn't get it, so what's the point. I only want to release music that people relate to. That's my thrill."

It was Lange who extracted from her the most personal song she's recorded, the brief "God Bless the Child," the royalties from which Twain has pledged to

children's charities. "Originally," she says, "that song was just 'Hallelujah, God bless the child who suffers.' I used to sing that line all the time when I was alone. I'd take long walks and just sing it out loud, let it echo. That pacified me."

"One day I was singing it, and Mutt heard it and said, 'That's such a beautiful melody, what is that?' and I said, 'It's nothing.' But eventually he convinced me to record it. After I did, I let go of it. I shared it, so I don't get the same thing out of it anymore."

So, she says, she is keeping most her other personal song snippets to herself. "There are some things I won't want to share."

Settling Down

Despite her unprecedented success, Twain seems remarkable clear-eyed, devoid of the extreme that tends to infect superstars. "I don't have a lot of highs

and lows," she says. "Even when wonderful things happen in my career, I think to myself, 'What's the matter with you? You should be doing cartwheels.' But it doesn't really get me excited. I don't ever get into

irrational states; I don't have angry explosions."

"She's so controlled and focused, it's spooky," says Mercury Nashville's Lewis. "It's probably a throwback to being a hungry kid and not wanted to ever be hungry again. It almost becomes a curse, because you don't sit back and enjoy your success."

Twain may finally do just that, now making a home of her own in her Swiss "freakin' château!" as she calls it. "I have privacy there," she says. "No one seems that interested in other people's business. I really like being normal, going to the grocery store. People know who I am, but they aren't interested in autographs."

She positively burbles about her new home's mix of bucolic--there are cows, sheep, and roosters nearby, and a stable she just fixed up for her five

horses--and worldly. "I think a lot of Europe is like a time warp," she says. "They've managed to progress with the rest of the world, yet they've maintained a culture that they fight for. Kids still play freely in the

streets here till dark."

Having all those rooms to fill in her new home has made her think about starting a family of her own. "It's certainly something I'm considering," she says. "This is a beautiful place to raise a kids." But it's not a

decision that she's taking lightly. "I realize what's involved," she says, "and that it isn't all fun.

There's a lot of heartache in having kids. You're lucky if they're healthy, first of all. And who knows what is to come after that?" She's also concerned that the demands of her career would interfere. "It's challenging when you're not settled. I know from my

sisters how all-consuming having children is. They tell me all the time: 'Hey--you can never wait too long!' "

Next year she hopes to release another album, plus a Christmas album. "A lot of people think we have all these tricks up our sleeve," she says. "You know what? The trick is hits! If you have a hit song, then you have a career carpet to ride on. Without it, the carpet is just not gonna float."

Though she seems the most natural celebrity to write an autobiography, she says, "I'm not sure I ever will. I can't tell my story without revealing my family's, and I don't think that's really fair. My career has exposed them so much already. We're just so, I don't know if simple is the right word, but we're northern Ontario people, and I don't think we'll ever be accustomed to the Hollywood thing." Speaking of Hollywood, she's been offered many movie scripts, but so far she has shied away. "I'm kind of afraid to try acting," she admits, "because I don't know if I'd be good at it, and I don't like doing anything I'm not good at."

But given her determination, she'll likely end up being good at anything she sets her mind to. "She always knew what she wanted, and when she wanted it," says her sister Carrie-Ann. "She's always driving toward something, her mind is always going, it never stops. She's always been that way."

During her concert at the Winnipeg Arena in Manitoba, a quiet section of the audience was sitting down in their seats. Twain ran around the stage demanding they stand back up. "Come on!" she hollered. "No lazy butts

allowed!" And as with everything else in her life, those 15,000 butts were soon doing exactly what Shania Twain wanted.

By David Handelman, Redbook, Dec/99 cover

Articles |

Covers |

Home

|