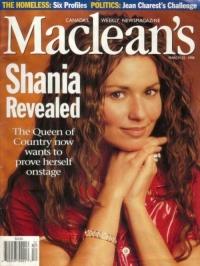

Shania Revealed - Cont'd

Twain, meanwhile, has handpicked a versatile touring band. The musicians all happen to be good-looking. They all sing, and most play more than one instrument -- including 27-year-old Cory Churko, a Vancouver fiddler-guitarist who has spent more time playing rock than country. "She wanted a young, energetic, rocking band," says Churko, who quit his job as a computer animator to enlist. Twain is categorical about her criteria: "I can't have anyone in the band who doesn't have my energy. I don't want people who have been on the road for years and are just doing it in order to do it. And I like a clean band. I don't like drugs. I don't like alcohol. I like to have clean-living people around me."

Twain, meanwhile, has handpicked a versatile touring band. The musicians all happen to be good-looking. They all sing, and most play more than one instrument -- including 27-year-old Cory Churko, a Vancouver fiddler-guitarist who has spent more time playing rock than country. "She wanted a young, energetic, rocking band," says Churko, who quit his job as a computer animator to enlist. Twain is categorical about her criteria: "I can't have anyone in the band who doesn't have my energy. I don't want people who have been on the road for years and are just doing it in order to do it. And I like a clean band. I don't like drugs. I don't like alcohol. I like to have clean-living people around me."

Is she not nervous about performing live? "I'm going to be overwhelmed at first," Twain admits. "But it's going to be fun, not scary." Although she has not toured since she became a star, Twain points out that she has 20 years of stage experience under her belt -- beginning at the age of 8, when her parents first started dragging her out of bed so that she could sing

(legally) at the Mattagami Hotel bar in Timmins after it had stopped serving liquor. Talk about paying your

dues.

"I love being in front of a live audience where I can control things," says Twain. "What I'm least comfortable with is the studio or anything contrived.

I'm never at my best on television. There's a row of cameras between you and the audience, and it's very weird, very confusing."

Shania Twain is onstage, rehearsing with her band for a taping of TNN's Prime Time Country. The TV studio occupies a wing of Nashville's Grand Ole Opry. As the nine-piece band runs through Don't Be Stupid, its young black drummer, wearing headphones in a Plexiglas booth, plays to a pre-recorded cue track. And although Twain is singing live, her vocals are perfectly synced to the

song's video, which is projected behind her.

The band plays with unerring precision, fiddles cutting in and out with the galvanized attack of a horn section. Twain, meanwhile, delivers her songs with polished moves that barely change from one take to the next. The toss of the hair, the hand-slap on the hip, each gesture seems built into the song. And as cameras swoop around the stage, she seems in firm command, knowing exactly where to look and how to act. Twain lays to rest any doubts that she can deliver onstage. Her voice may lack power, but she sings with melodic ease. Even when she is just testing the microphone with some a cappella phrases, there is a seductive luxury to her unadorned vocals. And as she searches for an elusive intimacy, the one thing she fusses over is the sound -- "too nasal . . . too much bottom . . . too much bite . . . can you take a bit of the hard edge off? . . ."

An hour after the rehearsal, the bleachers in the Nashville studio fill up with fans, who are taught how

to produce polite "golf claps" or "thunderous applause" on cue. As the show begins, a life-sized poster of Twain in the form of a jigsaw puzzle is lowered from the lights. Counting down the days to her appearance, a piece has been added each week, and now that she has finally arrived, the last remaining segment -- showing her belly button -- is stuck into place.

Between songs, Twain puts in time on the talk-show couch. She tells a story about taking the train to the

big city to appear on a TV show when she was 12. After a while, she realized she was going in the wrong direction. The conductor told her she could transfer at another station in six hours. "I said, 'You've got to stop the train right now because I'm going to be on TV.' So they let me off in the middle of the bush with my guitar, like a little hobo. I caught a train going the other way in half an hour, but I did think, 'What if the train never comes?' "

Twain's childhood reminiscences often have an apocryphal ring, but perhaps they have just become buffed by constant repetition. This much is known. She was born in Windsor, Ont., on Aug. 28, 1965, the second of three daughters of an Irish-Canadian mother, Sharon, and her husband, Clarence Edwards, who is of Irish and French descent. By the time Twain was 2, her parents' marriage collapsed, and Sharon moved with the children to Timmins, where -- four years later -- she married Jerry Twain, an Ojibwa forester and prospector. He adopted the children, who automatically gained First Nations status.

Throughout her childhood, Twain was aware of her biological father, and he occasionally visited her family. But she kept his existence a secret until 1996,

when The Daily Press in Timmins broke the story about the facts of her birth. There was a storm of controversy as Twain was accused of lying, and of enhancing her native heritage for the sake of her career. "It was very hard on my native family," she says. "I'm a registered band member. I've been part of their community since I was a little child. It's very

hurtful to know there are people who want to unravel all that."

When asked why she didn't tell the truth from the beginning, Twain's consistently perky composure gives way to a burst of anger. "Half the people in my life didn't know I was adopted," she says. "Why should I have told the press? It frustrates me no end, I can't tell you. I have never referred to Jerry as my stepfather. I never even referred to Clarence as my father, and I didn't care if I was ever in contact with

that family again." Then, she adds: "It's never been anissue for me, but it's an issue for everyone else all of a sudden. It's like a big black hole."

In his recent book about country music, Three Chords and The Truth, U.S. author Laurence Leamer went so far as to call Twain's life story "a brilliant reconstruction," claiming that she has exaggerated the poverty of her childhood. Twain says that in fact the reverse is true: "Let's put it this way. I'm not sugarcoating, but I've revealed very little of the true hardship and intensity of my life, and that's the way I'm going to keep it."

As a child, the singer recalls, she sometimes went for

days with nothing to eat but bread, milk and sugar heated up in a pot. "I hardly ever took a lunch to school. I'd say I'm not hungry. Or I'd bring, like, mustard sandwiches." But Twain has fond memories of learning to hunt and trap in the bush with her father -- although she is now vegetarian. And alone in nature, she would create her own world. "I'd take my guitar for a walk and go to a field or the river and write songs," she says. "As a kid I had three dreams: to live in a brick house and eat roast beef, to be kidnapped by Frank Sinatra, and to be Stevie Wonder's backup singer. It was never my dream to be a star. That was my parents' dream. I guess they prayed real hard."

Twain was a reluctant performer, but her parent were persistent. By her early teens, she was popping up on programs such as The Tommy Hunter Show. But only when she discovered rock 'n' roll did she begin to enjoy the stage. "I couldn't hide behind my guitar," she says. "I sensed a freedom that I'd never sensed before." Twain completed high school while working at McDonald's and playing bars. Meanwhile, her parents started a reforestation business, and from age 16 she spent summers in the bush, learning about chainsaws and seedlings, until she was supervising her own native crew.

In 1987, the death of her parents changed everything. Twain, then 22, was suddenly forced to become a mother to her younger sister and two teenage brothers. Her manager at the time, Mary Bailey, came to the rescue with a steady gig at the Deerhurst Resort in Huntsville -- as a lounge act and as a singer in glitzy cabaret revues such as Viva Vegas. Twain paid her dues for three years at Deerhurst. And Bailey lured a Nashville producer up there to see her perform -- which led to her first record deal in 1991.

The first album, Shania Twain, had modest sales of about 100,000 copies. But it led to the romance with Lange, which started as a songwriting relationship over the phone. They finally met face-to-face in Nashville, and married at the Deerhurst six months later. Lange, meanwhile, helped finance The Woman in Me, a $700,000 work of studio wizardry touted as the most expensive country album ever recorded.

Since then, reports of ruin have swirled around Twain's marriage. "People in the industry were calling my management all the time asking, 'Are they really divorcing?' " she recalls. "Most people thought we were unlikely to succeed. My family were like, 'You just met this guy, you can't get married.' " Twain adds that You're Still the One is about Mutt -- and "the nice feeling that we've made it against all odds."

They do seem an odd couple. She spends much of her life in a professional romance with the camera; he is so obsessively media-shy that it is impossible to find a published Mutt Lange picture or interview. The South African-born producer never shows up with his wife at industry functions where he might be photographed. At the TNN show in Nashville, however, a backstage sighting -- of a blue-denimed figure in his 40s, tall and handsome with a shag of blond hair -- confirmed that he does, in fact, exist.

How can such a reclusive husband get along with such a public wife? "I make my living partly by being a celebrity," says Twain. "But I would love to have his life, to do the music and not have to be famous. I'm more private than people realize. I'm not that easy to get to know. My husband's the only one who really knows me. To get through the kind of life I've been through, you have to be strong, and it's wonderful when you find the right person who can share everything about you."

Whatever pain lies behind Twain's nearly seamless public persona, there is little evidence of it in her

music. "It's not pure emotion. I mould it so it can be

applied to people's lives. But I write a lot of music I

don't share, for the same reason people have diaries. I just express myself. It's not a creative thing. It's therapeutic."

Twain's celebrity has brought its own pain to her family, and not just the native heritage controversy. Over the years, her younger brothers, Mark and Darryl, now 25 and 24, have been in and out of trouble with the law. In 1996, after they were caught trying to steal cars from a Toyota dealership in Huntsville, everyone from the CBC to The National Enquirer chased the story. "It's difficult for them to be exposed if they do anything wrong," says their sister, "but at the same time it helps keep them straight." Her brothers, she adds, are now working in the bush cutting timber.

Back in the Grand Ole Opry studio in Nashville, the host of TNN's Prime Time Country regales his audience with tales of Twain's days as a forestry worker in an exotic place called Timmins. Getting her to put on a yellow hard hat, he challenges the singer to a log-cutting contest. Picking up one of two small electric chainsaws, she says: "This is kind of dinky.

It's what men would call a woman's chainsaw." They start their engines. And as the crowd roars, Twain cuts through her log in seconds, leaving her host in the sawdust -- and her legend intact.

Maclean's, March 23/98, By Brian D. Johnson

Back To Page 1

Articles |

Covers |

Home

|