Even Showgirls Get the Blues

From Dirt-Poor Childhood to Glitzy Lounge Singer to The Queen of Country Pop, she's made it all look easy. But it hasn't been.

From Dirt-Poor Childhood to Glitzy Lounge Singer to The Queen of Country Pop, she's made it all look easy. But it hasn't been.

On a late morning in early summer, Shania Twain decided to catch a few minutes alone with her horses. This was at her place way out in the Adirondacks, past Lake Saranac, New York, near Cat Mountain. The place is actually a twenty-square-mile estate, with an electronic security gate at the entrance, lots of forest, a great big lake and a road that snakes back into the middle of nowhere. Overlooking the lake is a

giant wooden structure, freshly built, composed of a world-class recording studio, apartments for guests, room for the Twain Zone business offices and all the usual amenities; and this isn't even the main house, which has yet to be built, though there are steps leading up to where it one day may be.

It was almost noiseless out there, and deeply serene. For a while, no one knew where Shania was, and various nervous Twain personnel scurried about. Then she ambled

down from the stables with her hair in a topknot, in jeans and very little makeup, and swung inside the back of the bus that would shortly take her on her first-ever world tour but that now carried her into Lake Placid to practice her stage act.

Even without a tour, Shania had gone from being the biggest thing in country music, with 1995's The Woman in Me (sales: 10 million, the most of any album by a female country artist), to among the biggest things in both country and pop, with last winter's Come On Over (sales: 4 million and rising), both of them produced by her husband, Robert "Mutt" Lange, who had also produced hit records for Def Leppard and Michael Bolton. In this regard, she was almost as much of a crossover sensation as Dolly Parton or Garth Brooks - more, really, since Dolly and Garth sold like pop stars but never shed their corn pone. Shania, though, had almost too little country for some of her critics and the numbers to suggest that she might be too big for that world, anyway. During one week in May, her single "You're Still the One" was both the Number Two pop song and the Number One country single in America. Meanwhile

MTV began playing the song's video, following VH1's lead. Then, in Detroit, Shania sold out the Pine Knob Amphitheater in just twenty-nine minutes, a pace matched only by the Who, Metatlica, Bob Seger and Jimmy Buffett.

Naturally, this kind of success had not occurred overnight, nor without controversy and the pissing off of various folks. Nor, in Shania's case, did it happen without a major personal tragedy; her parents were killed in a car accident when she was twenty-one, leaving her to care for three younger siblings. But looking out her bus window at the passing countryside, she did not speak of these things now. Pleasantly, she settled in and started to give an accounting of herself as, among other things, a simple Canadian girl from a rugged gold-mining city called Timmins, in the frigid northern reaches of Ontario, 500 miles beyond Toronto. She was a shy teenager, a little at odds with her sexuality, even angry at times over the unwanted attention of boys. She said that she preferred not to

think of herself as a country artist or as a pop artist but, simply, as an artist who had done what ever it took to get work." She said that for as long as she could remember, she had but one dream. "My goal has always been to be international," she said. It's what I have wanted right from the start." To that end, she wrote songs that wer clever and decidedly commercial and used her looks to give them visual punch, and she made no apologies for either.

She paused for a moment, thinking about her looks. Like many beautiful women she was canny about what she had and yet also keenly aware of her flaws. "I don't see

anything in particular in the mirror," she said with a shrug. "Pretty plain. Pretty simple. I have good teeth. Strong teeth. I floss all the time, twice a day. My eyes are too small. Have good cheekbones. My legs are stumpy. A dented nose." She winced at the mention of her nose, for she would not have known it was in this way if not for photographer John Derek. Shania had asked him to take pictures for her second album, some three years ago. He agreed and arrived with Bo. In Shania's eyes, Bo was still perfect. In John's eyes, Shania was anything but. "He sees me," Shania recalled, "and I'm like a monster to him. It wasn't funny at the time.'Somebody give me a knife!' he said. I've got to cut that nose off!"'

Shania sighed and swept back some uncooperative strands of hair. During the shoot, which took place before Shania was a success, and during their time together

afterward, Shania, John and Bo became friends. Now John was dead. He'd died just two days ago of a heart attack. Within an hour of his death, Bo called with the news, It struck Shania hard, but that night she took to the practice stage anyway. "It's such a shock," she said. "You know, kind of a drag. And then I had to do the rehersal.

I didn't want anybody to see me, 'cause I just hate that affecting me." She considered her words. For a moment, she looked a little befuddled, like maybe she had misspoken or said something unfortunate. "But of course she went on it has to affect me you don't want to say, I'm not bummed out' or ' I have to forget that I'm bummed out.' It was just a terrible thing. It was a very sudden thing. He had a massive ... some kind of a ... and he died very quickty. So now Bo's alone. It keeps freaking me out a bit."

When you think of it, it is kind of a miracle, Shania Twain in the same league as the Who and Metallica. And it doubtless swelled the hearts of not only the Shania

publicity machine but also the Jon Landau management team, which began working with Shania in early 1997 and which also works with Bruce Springsteen and Natalie

Merchant. No doubt none of this mattered much to Shania, just as it didn't mean all that much to her to learn, in 1996, that her Woman in Me album had broken a sales record long held by Patsy Cline. "I don't get all that excited," she said. "It's a great thing. But you know what? I don't take a lot of pride in those things, for some reason. It just doesn't mean that much." She kind of snorted and laughed. "My poor manager gets so excited," she continued. "And I'm not a lot of fun. I'm like,'That's great. Now let's move on.' "

If Shania is unruffled by show-business milestones that would make other performers insufferable, she probably has her reasons. Her father, Jerry, an Ojibwa Indian, and her mother, Sharon, an Irish-Canadian, raised her in a medium-size city in northern Canada, home to some of the largest gold mines in North America, 2oo lakes, a year-round view of the sparkling northern lights, temperatures that can reach minus-forty degrees, many, many ice-fishing fanatics, a subpar educational system

and more than its share of unemployed.

Indeed, Jerry, a forester and prospector, never had steady work. There were four kids in a house with three bedrooms, and the family was poor. When there was milk

around, a rare enough event, it was doled out in exact portions. At school, Shania envied the apples and roast-beef sandwiches of the other kids; she never had too many apples; between her two slices of bread was only mayo or mustard, nothing else. She lived in fear that her teachers would find out that her folks couldn't afford to feed her and she'd be taken away. That, she said, was her only worry. She didn't care, apparently, that she was sometimes desperately hungry. "I don't look at it as a bad thing at all," she said. "I don't regret my childhood. Learning to make mustard

sandwiches was something just to get me through the embarrassment, to help me avoid humiliation." If someone said to her, "That's so sad," she would say, with force, "It's not sad." She loved her mom and dad. She knew that they could very easily have lived a better life if they went on the dole. But her dad was determined to make his way on his own. "It was a pride thing," she said. "I respect him for that, and I don't feel bad for myself, even for a second."

If Shania didn't, however, her mother did. Because she often couldn't feed her kids or even keep them warm or even keep their clothes all washed (hand washed, in the

bathtub), she sometimes got into bed and could not get out, she was so depressed. "Tough times, man," Shania said, rather coolly, looking back at it. Even so, Jerry and Sharon had their dreams, and their dreams mostly revolved around Shania, who from the age of three could sing with vibrato and had a good enough ear for harmony. She took up the guitar She wrote her own songs. She was quite something else, and the older she got, the more Sharon thought that this kid could make it big.

Shania listened to her parents' favorites: Wayton Jennings, Willie Nelson, Dolly Parton,Tammy Wynette; but, as well, to the Mamas and the Papas, the Carpenters, the Supremes and Stevie Wonder, for whom she fervently wanted to be a backup singer. For a poor, shy girl, music was a refuge, her hidng spot. Indeed, she didn't want to be a star. But that's what her mom wanted. At the age of eight, then, Shania played guitar and sang at community centers and at senior-citizen homes and at the bar inside Timmins' Mattagami Hotel, where she'd get up onstage after-hours and carry on bravely, surrounded by cigarette smoke and a whiskey-fume haze.

One person who heard her perform during this time was Mary Bailey, a fellow Canadian, a country singer herself and eventually Shania's first manager. "She was

this little girl who got on a stage with a guitar and just blew me away," Bailey recalled. During high school, Shania spent her summers leading a reforestation crew for her dad - reportedly, she wields a mean chain saw - and working at a McDonald's. She fronted a rock band, playing the usual Top Forty stuff, Journey, Cheap Trick and Pat Benatar. She rarely drank and never did drugs, which made her the only one in her circle of friends to be such a square, though no one really cared. "I mean, I knew that that was black hash and that was blond," she said. "But I was so high on music and Rush and Pink Floyd.

We're all going to see Pink Floyd, and I'm like, 'You guys want to put a few things on your tongue, do acid, you just go ahead.' Meanwhile, I probably looked high. I used to really rock out. I'd get people coming up to me saying,'Do you do drugs or what?' I never did, but I looked like I did."

In 1987, when Shania was twenty-one, her world was turned upside down: Her parents died in a headon collision with a fully loaded logging truck. "I called her," Shania's sister Carrie-Ann, 30, said recently. "She was in Toronto, pursuing her music. I just remember pretty much saying what happened and hanging up the phone, and the next thing, it seemed that she was sort of there." Indeed, over the years, when talking about it, Shania spoke only about what happened, the events, and about what happened next, and never about what was going on deep down inside her. She

looked for solace in work, took care of her younger siblings and just got on with her career. Up until this time, it seemed as though she would become a rock musician. Afterward, she first tilted toward Las Vegas, then marched straight into country.

The suggestion has been made, numerous times, that the dire circumstances of Shania's youth have been enlarged upon and embellished. "They have an apocryphal ring," went one report. Wrote author Laurence Leamer in his book about country music,Three Chords and the Truth, "A brilliant reconstruction ... a virtual past." The

idea, of course, is that of such out-of-poverty stories are great myths made, and that Shania's use of some basic hardships was a marketing masterstroke designed to give everyone alive something about her they could relate to or admire or pity, which would in turn lead to increased record sales and eventual worldwide musical domination.

"Well, I want to set that guy [Leamer] straight,"Shania said one afternoon "Because you know what? The reality is, if anything, I'm easy on the subject. The only reason that I talk about it at all is because I have this charity I support [Kids Cafe/Second Harvest Food Bank, which provides meals for underprivileged children] and I want to make people aware of it." She made a sour expression and blew a raspberry through

her lips. "It's all very true," she said. "Like, as if I'd make any of it up for commercial gain! I have not fabricated anything in my life."

Maybe that was true, but little minds didn't agree. In early 1996 the Timmins newspaper came out with a startling report. It started off, "The Daily Press has

learned that Twain has woven a tapestry of half truths and outright lies in her climb to the top of the country charts." The prevarications, it turned out, all revolved around a single fact: that her biological father was not Jerry Twain, as she had always maintained, but a French-Irish railroad engineer named Clarence Edwards. This made Jerry her adoptive father, and, in turn, made an issue of one other matter; Shania's bloodline. She was not, in fact, of Ojibwa Indian descent; her heritage had been conferred upon her through adoption.

All hell broke loose. There was a storm of bad publicity in Nashville, which likes to think that it values integrity and roots more than anything; there was more storming in Timmins; there were threats of lawsuits; and all the usual modern-day fallout. It was

ugly. And if you swore your allegiance to emotional truth over literal truth, it probably never should have happened. Two years later, Shania still couldn't understand the fuss: "The reality is that, to me, it's a very non-issue. Someone just took advantage of a situation to get some kind of recognition for it." She shook her head and pushed at a bowl with some huge, glistening strawberries in it and didn't seem especially hurt by what the Timmins paper. "I'm very sensitive about a lot of things, actually,"she said

after a while. "I don't come across that way. I tend to be very frank and bold. I'm sure I come across as very driven, very direct, very focused, and none of those things encompass any real sensitivity. But I'm quite a sensitive person."

The dog came sniffing around. Shania used to have a burly bodyguard, but having a bodyguard got to be a little much, she has always valued her privacy. A burly dog was much better, His name was Tim, a German Shepard one of those fancy, insanly expensive Shutzhund-tranind dogs: not a killer, but deeply motivated to love and

protect one person- in Tim's case, Shania, though Mutt seemed to be Ok in his book, too.

"That's enough, Tim, you little Nosy Parker," Shania said. "You go plotz. Go plotz. It's Ok." Tim continued to nudge Shania. "Phooey!" she said. He laid himself down across the tops of her feet. What happened after her parents died was this: She didn't crumble .

"I became very hard for quite a long time; . I was so numb. Nothing penetrated. It was a very difficult time. But boy, oh, boy, did I ever get strong." She had her three younger siblings to take care of, which she did by calling on Mary Bailey, who helped her get a job at an Ontario resort as a lounge singer and a member of a

rhinestone-studded, feather headdress wearing, leggy Las Vegas-type revue. She was not a glamour puss. She could look washed out pinched. And her name wasn't

Shania. It was Eileen, the name she grew up with But around this time,Bailey helped Shania cut a demo of original tunes and get it listened to in Nashville, which liked what it heard, which led to a request for a new, more suitable first name (taken from an acquaintance, the 0jibwa name Shania means "I'm on my way," the ultimate signifigance of which has been lost on no one) It was noteworthy for one thing, though: the video for the song "What Made You Say That." It featured Shania and some stud twirling around a tropical beach setting and the first major sighting of

Shania's navel, which she would flaunt to great effect in subsequent videos. In London, seeing the video and Shania for the first time, Mutt Lange was, by all

accounts mesmerized. The way the story goes, he had woman, so he called Mary Bailey and word for Shania to call him. . Well, neither woman knew this Mutt from

Adam - he was a famous not a famous country producer, so maybe Shania would get back to him, maybe not. But he kept calling till he got her on the phone. It was

definetly a force that brought us together,"

Shania said once. Some went through a lot of anger and frustration over that as a teenage girl." She then started talking as she sometimes did, in the second person, as if what happened to her had in fact, happened to someone else. The guys see a girl

who's developed up there maybe they touch you up there and you really feel very invaded. And so, you know what? The easiest thing is to just cover them up, trying to get rid of the bounce factor. And that's what I did I wore three shirts at a time. I tied my self in. And now I've got a song on this album called 'If You Want to Touch Ask!' Well, it stems from that. I could have made it a much deeper, darker song. But

that's not the way I go."

I think her approach to life experiences is to strive for positiveness that animates most of what she writes," said Jon Landau. I think that's her philosophy. She works her butt off. She's very results oriented, no-nonsense. And, to me, she is utterly real."

Recalling the old days, Mary Bailey said that Shania lived for her music: "She's very similar to an athlete going for the gold. I'm sure she's got a frivolous side to her, as I'm sure we all do, "The truth is," Shania said later, "I'm distracted by very little besides music. When it really gets down to it, for instance, I am not a sexual person. My mind isn't there. I mean, I'm very satisfied, and I'm not hard to satisfy. But I'm not one of those people who just always has this desire. I don't think like that. Never did. Always had total control of my sexual habits.

"I'm very conservative, really," she went on. "I'm not that physical. I mean I am with Mutt, of course, and with my dog. But beyond that, not even with my family. I'm just not one of these hug everybody people. I'm better now than I was. Used to be, I didn't even want my mother to hug me. I used to hate it.

"I will only wear a bathing suit with a wrap, unless I'm really being daring", she continued. "Oh, sometimes I get free spirited enough to actually say, I don't give a shit!' But it doesn't happen often. Like, even if I was the only person on the beach that wasn't topless, I would not take my bathing-suit top off. My husband would go, 'Why not? Every other woman on this beach is topless But I couldn't. It's just the way I am."

Shania stayed on the bus, just the way she was. On her videos, she was sassy, flirty, roundabout and sexually carefree. In private, she was none of these things. "She's very quiet, very reserved, and very cautious about who she lets in," said Bailey. Shania knew perfectly well that she was perfectly split in this way, and it did not seem to stir her She could talk about it with ease and even seem amused that she

wasn't more sexual or even more warm. She was simply the singer doing whatever it took to get work, and if sometimes how was onstage wasn't how she really was, that didn't make her any less her own person, any less pure.

It was almost time to go practice. Soon she would be playing before Who- and Metallica-size crowds. Since she didn't tour for her first two albums, this would be a first for her. She wasn't worried. One way or the other, she had been performing since she was three. She had become the kind of woman who has a motto. Her motto

was "A happy heart comes first, then the happy face." It's what she strove for. Mostly, it's what her songs were about and probably why they sold so well, making

her nearly international, because so many people were living the motto the other way around, face first, and it wasn't workng and maybe they could sense that Shania was onto something better.

It was because of that motto that she and Mutt recently considered putting their huge Adirondack place up for sale and made plans to move to Switzerland. It was the

privacy thing. They could no longer have happy hearts here, Mutt for his own private reasons and Shania because, even in the boondocks surrounding Lake Placid, she could not find the room to just be herself.

"I mean, look," she said. "I live in the most remote area you could possibly live in, and yet everyone knows everything about me. I come into town wearing a hat and

sunglasses, and I'm still recognized. It must be my mouth or something. Anyway, you just want to be one of everybody else. Especially me. I know I'll get more privacy over there; it'll be nice to be able to get on a plane and get off and then be in a completely different world. Because of the type of person I am, I'll enjoy that."

Because of the type of person that she is, she didn't touch any of the magnificent strawberries that were in a bowl on her bus, and they were looking a little dried up and not quite so plump. At one time, Shania couldn't afford a strawberry of this sort; now she could afford to buy them and not eat them. It was OK. It was good to have them. They were still there, in case she changed her mind and suddenly, for instance, needed one.

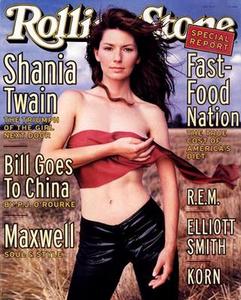

Rolling Stone (cover); Sept 1/98 issue

Articles |

Covers |

Home

|