Against All Odds

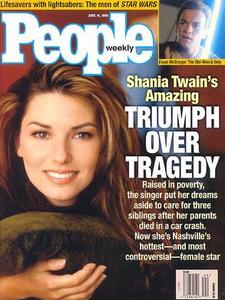

Overcoming a past filled with poverty and sudden tragedy, Shania Twain emerges as a happily married pop superstar.

Overcoming a past filled with poverty and sudden tragedy, Shania Twain emerges as a happily married pop superstar.

Shania Twain has strange dreams. Sometimes the parents she lost in a car crash more than a decade ago, when she was still known by her given name, Eileen, appear to guide or chide her "I had a dream last night," Twain recounts, "where I was sleeping and my mother said, 'Okay, Eileen, you have to get up now.' I pulled the covers off, and there was a video camera on my face. They were in my bedroom filming me, and I just couldn't believe that my mother would do this to me. I said, 'Mom, what's going on?' And she said, 'Did you forget? They're filming you today."' Pondering the dream, Twain suggests, "sometimes you feel your career over runs your personal life."

For the Grammy-grabbing singer known for her bare-belly-button wardrobe and relentless drive, the two might seem the same. Twain, whose childhood sleep often was disrupted by late-night club dates ("Eilleen," her mother would whisper as she awakened her, "you have to get up"), has been tirelessly touring the U.S. and Europe. Her third album, Come on Ovei; like her 1995 breakthrough CD, The Woman in Me, has sold more than 10 million copies and just spawned yet another Top 10 hit, "That Don't Impress Me Much." Those numbers put Twain, 33, in the same league as Whitney Houston and Mariah Carey - and far above any previous country queen. "With Shania, I see progress," says June Carter Cash. "She has opened up a lot of space for future female country singers."

Pivotal to Twain's crossover success is her husband and producer, Robert John "Mutt" Lange (for whom Twain wrote last year's smash single "You're Still the One"). A rock and roll veteran who has produced multiplatinum albums by Bryan Adams, Def Leppard and Michael Bolton, the South African Lange, 50, first spotted Twain in 1993 while watching one of her early videos. Smitten, he called her in Nashville from his London home, and the pair spent the next three months writing songs over the phone. By then the twice-divorced Lange was determined to stay single, but Twain turned him around. "I had never seen Mutt like that before," says Bolton. "He was as focused on Shania as he was on his work. He just had an instinct that she was it for him." The instinct was mutual. Recalls Twain's sister Carrie-Ann Brown, 31, who lives in Huntsville, Ont.: "She said to me, 'He's the one.' There wasn't a question in her mind from the beginning."

The couple, who married in December 1993, nine months after that first phone call, are rarely seen together. Lange is notoriously publicity-shy: In a recent preemptive strike against the press, he bought the rights to nearly every photograph ever taken of him. "He doesn't want to be a celebrity - he just wants to be a producer," says Twain, whose latest collaboration with Lange is the single "You've Got a Way" from the Notting Hill soundtrack. "So he avoids the spotlight. That's why people think he's a recluse." Her demanding touring schedule also keeps the couple out of the camera's way. "We're apart more than we're together;" says Twain. "It's very, very difficult. Sometimes I think, in five to 10 years, when I'm not traveling as much, what's it going to be like then. It's that scenario when one or both of a couple retire, and then they don't know what to do with each other. They're together too much." But since Twain and Lange don't have that problem, people speculate. "I get a call every few days from someone who has heard they have broken up," says Mercury Records Nashville president Luke Lewis. "I would be totally shocked if it happened."

By now, Twain must be as accustomed to swirling gossip and sniping as she is to sold-out shows. Her revealing stage costumes and pop-rock bent make her a predictable target for the country establishment. The impoverished childhood she relates in interviews has been challenged by those who knew her then. Her claim to North American Indian heritage (in 1991 she changed her name to Shania, the Ojibwa word for "I'm on my way") has been mocked. And even the saddest and most courageous part of her story - the real-life Party of Five that began when, at 22, she returned home to rear her younger siblings - is disparaged by some.

The singer's complicated odyssey began in Windsor, Ont., in 1965, where she was born Eilleen Regina Edwards, the second of three children of Clarence Edwards and his wife, Sharon. Her parents divorced when she was 2, and Eilleen moved with her mother and two sister - Carrie-Ann and Jill to Timmins, a gold-mining town 500 miles north of Toronto. In 1971, Sharon married Jerry Twain, an Ojibwa forester and mining prospector. Together the couple had two sons, Mark and Darryl, and Jerry adopted Eilleen and her sisters and later got them membership in his First Nation tribe.

"My dad's side of the family was the side we grew up with," says Twain.

"So it was the Indians that were really our family."

That made Twain's biological father the odd man out. "We maybe saw him three times," says Carrie-Ann. "We don't even know him." With Jerry at the head of the household and frequently between jobs, the family often lived on the brink of poverty; "As a girl, I would go snaring rabbits for food," says Twain. "I'd go hunting [for moose] with my dad in the bush. The basics in our lives were different from a lot of the basics in our white friends' lives." As an example, Twain, who moved with the family from Timmins to nearby Sudbury (pop. 92,000) at age 8, recalls a time when a friend slept over. "She went into the fridge the next morning, got the cereal out and started pouring herself a tall glass of milk plus milk in her cereal. It was such an indulgence in my eyes. So I grabbed the glass and said, 'You can't have that. We have to share.'"

Some people believe Twain is milking, if not embellishing, her rags-to-riches story. "They had a house, a car, a TV," says Lawrence Martin, a family friend in Sudbury. "I never saw them as being as poor as described in interviews. We were all poor, working, struggling." And in 1996, The Daily Press in Timmins ran a story accusing her of overstating her Ojibwa heritage by not disclosing that Jerry was her adoptive father. A controversy ensued that spawned national headlines and temporarily tarnished her image. "I don't know why they have to challenge me," says Twain. "Maybe there were people who knew us during a time when my dad was getting a regular paycheck or both my parents were working. We went in and out of difficult times; we weren't always starving." As for the alleged North American Indian deception, notes Twain's former lawyer Richard Frank: "It was very upsetting to her when it came out. She looked upon [Jerry] as her father and she was very proud of her Ojibwa heritage. Her biological father had [left] her mother very early. Eilleen has just drawn a curtain over that part of her life. I think it was terribly painful to have that curtain ripped open. I think she felt that it dishonored her father who raised her and sought to diminish his role as a father."

One aspect of Twain's childhood is indisputable: her hunger for music. At home she spent much of her time singing along to Anne Murray and Charley Pride hits on the radio. At her parents' urging she began performing around Sudbury at age 8. "They dragged her to bars and festivals and family gatherings," says neighbor Martin. "Her mom drove her all over, scheming where to take her next." Often that was onstage at bars after last call. "I remember my parents coming into the bedroom late at night to fetch her from the top bunk to go sing," says Carrie-Ann. Her parents' ambition and drive, particularly her mother's, eventually rubbed off on Twain.

Back in Timmins, where she attended high school, Twain joined a Top 40 cover band called the Longshot. Soon, she was singing with the group five nights a week at a local lounge and working part-time at McDonald's. But while she exuded star power onstage, at school she was withdrawn. "I felt invisible a lot," says Twain. "I actually wrote a song called 'Feeling Invisible.' I was athletic and into music and not really socializing, and I'm sure a lot of it was because I was introverted. Her upbringing also played a role. "The whole family tends to be a little standoffish," says Carrie-Ann. "There wasn't a lot of hugging and grabbing between our parents."

After graduating from high school, Twain quit the Longshot and in 1987, at 21, moved to Toronto, where she worked as a secretary while singing in clubs. But her days as an independent career woman ended abruptly that November when her parents were killed in a head-on collision with a logging truck on an Ontario highway. (Twain's brother Mark suffered minor injuries in the accident and was hospitalized.) "I felt totally lost," Twain told PEOPLE in 1995. She promptly quit her job in Toronto and hurried back to Timmins to take care of her younger siblings. (Older sister Jill by then had a family of her own.) "I was on automatic pilot, doing what I had to do. It was a stressful time," says Twain. "Eilleen was always sort of a mother figure," adds Carrie-Ann. "We just knew she had to take charge. There was no other way."

Looking after her younger sister and her brothers - Mark, then 14, and Darryl, 13 - wound up being a test of endurance. "She was really strict with us," Mark, now a computer technician in Vancouver; told PEOPLE in 1995. "She was scared." (Darryl is an electrician in Edmonton, Alta.) And insecure. "I was overwhelmed with a lot of decisions," says Twain. "I had to deal with my parents' mortgage, and I didn't even know what a mortgage was." But, she adds, "what I learned through all of that was how strong I was capable of being. I didn't fall apart. I kept it together; paid the bills, took care of the kids, did the groceries, cooked and cleaned and still kept down a job. I always had a feeling things would work out. I still feel that way about life."

Super sis ended up selling her parents' home in Timmins and moving the clan into a rented house with no running water in Huntsville. There, Mary Bailey, a friend of their mother's, found Twain a job performing at Deerhurst Resort as a sequined cabaret singer with big hair. "She would bring these big jugs of drinking water from Deerhurst," says Carrie-Ann. "We would all jump in her [truck] and go down to the river to bathe. We hated it."

While roughing it at home, Twain was glowing onstage at Deerhurst. In 1991, Bailey, who by then had become her manager; persuaded attorney Frank to fly to Toronto to check out Twain's act. Impressed, Frank coaxed Nashville producer Norro Wilson to work on her demo, and later that year Twain left for Nashville. She also left behind her brothers, who had finished high school, and Carrie-Ann. Adopting the name Shania from a wardrobe girl at Deerhurst (her friends and family still call her Eilleen), Twain released her debut album, Shania Twain, in 1993. It sold only about 100,000 copies, but with Lange on board, 1995's The Woman in Me produced eight country hits, including "Any Man of Mine" and "Whose Bed Have Your Boots Been Under?"

These days, Twain's own boots rarely stay under one bed for long. Off the road, she vacations with her husband in the Caribbean or at their retreat in southwest Florida. But they spend most of their time in Tour-de-Peilz, Switzerland, at their l9th-centuuy manor house that they bought in December after putting their 3,000-acre estate in Upstate New York on the market for $7.5 million. "There was a zoning problem," says Twain of their relocation abroad, which some speculate had more to do with the lower taxes there. "My husband wanted to do a lot of landscaping. And that landscaping wasn't permitted."

Despite the chronic separations, Twain and Lange remain kindred spirits. Both are treetotaling vegetarians and horse lovers, and he reportedly has introduced her to the principles of Sant Mat, an Indian form of meditation. Most important, they agree to put work first, which means postponing a family. "I'd like to have kids, but we're not planning at this point," says Twain. "Right now I'm dedicated and committed to my career." Perhaps she'll never be ready for motherhood. "She says that one day she wants to have kids," says Carrie-Ann, who is herself a mother. "Then," she adds half jokingly, "she comes and visits and changes her mind."

Having children, after all, might tamper with Twain's trademark abs, which she flaunts at the drop of a ten-gallon hat. Much of Nashville doesn't have the stomach for such racy exhibitionism and has struck back. Despite her success, Twain has never won a Country Music Association award. "She hasn't won the awards she should have," says Nashville journalist Michael McCall. "It hasn't quite happened for her as it has for Garth or the Dixie Chicks." Country star Reba McEntire agrees: "She's been at the top of the charts for two years, and she still hasn't gotten the pats on the back that she deserves."

At this year's Grarnmy Awards, Twain shocked the town by squeezing into a skintight dorninatrix ensemble to purr "Man! I Feel like a Woman!" And yet, she says, "I've never been out to offend people or do things for the sake of being different. But you can't please everyone. As long as I'm comfortable and I like what I see in the mirror, I go for it." McEntire, for one, thinks she should: "She's got the body, and she's got the looks."

In July, after her tour ends, Twain will join Lange in Switzerland, where they'll start work on an album of Christmas music. It probably won't contain any honky-topic tear-jerkers about hungry holidays past. "As much as she has in common with the Loretta Lynns of the world," says journalist McCall, "she doesn't sing the heartbreak songs. She doesn't want to look back at that time in her life. She wants to be positive and move forward." That means donating a portion of the proceeds from each of her concerts to charities that help feed hungry children. It's a nod to her impoverished past, but mostly it's a celebration of now. "When I look back at my childhood, I don't carry that grief with me," she says. "I feel like I was another person. I've gone through some very dramatic stages in my life, and I feel three different people lived through those stages. It's funny," she adds, "I often feel like I'm on my third lifetime."

Jeremy Helligar, People Weekly, June 14, 1999

Articles |

Covers |

Home

|